Forty years ago, India passed the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act- the first central legislation to tackle the air pollution problem in India. At the time of enactment, air pollution was just starting to get recognized as a credible threat in major cities in India and was being attributed entirely to industrial and transportation sources. Today, however, the problem has taken on a new form, with several more sources like household emissions, road and construction dust, and biomass burning getting acknowledged for their contributions. Further, air pollution in India has finally been recognized as a public health threat to the entire country and not just to urban areas, with over 99.9% of the population being exposed to PM2.5 levels above the WHO standards. Does the Air Act have enough teeth to deal with this crisis? What has it accomplished over the last four decades? Does anything need to be updated to keep up with our understanding and nature of air pollution in India?

The history of the Air Act is intertwined with international events that have paved the way for environmental discourse. The foremost example is the Stockholm Conference for Human Environment (1972) where 113 countries vowed to enact policies to protect natural resources. In response to growing international consciousness, the Indian government enacted the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981 , and the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. After decades of handling environmental issues such as pollution on an ad-hoc basis, the passage of the Air Act was a significant event with the potential to transform air quality governance in India. The primary objective of the Air Act is ‘preservation of the quality of air and control of air pollution.’ The Water Act, 1974 had provisions to set up Central and State Boards to regulate water pollution. With the enactment of the Air Act, the mandate of these Boards was broadened to include regulation of air pollution as well.

In forty years since its promulgation, the Air Act, stands largely true to its original print, with the substantive framework of the Act remaining unchanged. In contrast, the Clean Air Act 1963 of the United States is continually updated to ensure that it appropriately responds to new sources causing depleted air quality and to scientific developments in the field of air quality management. This begs the question: is the Air Act a timeless piece of legislation, or has the modern Indian air pollution problem taken on a new form, requiring a fresh set of laws to control it?

The Act has been crucial in developing a framework for regulation of air pollution. It lays down a mechanism to monitor pollutants, set standards for emitters, devise plans for clean air and creates an enforcement mechanism through the PCBs. At the time of enactment, the Air Act empowered the State Governments to declare any area or areas within the state as an ‘air pollution control area’ for the purpose of the Act. However, by the mid-to-late 1980’s, State Governments began to notify entire areas of the State as an air pollution control area.

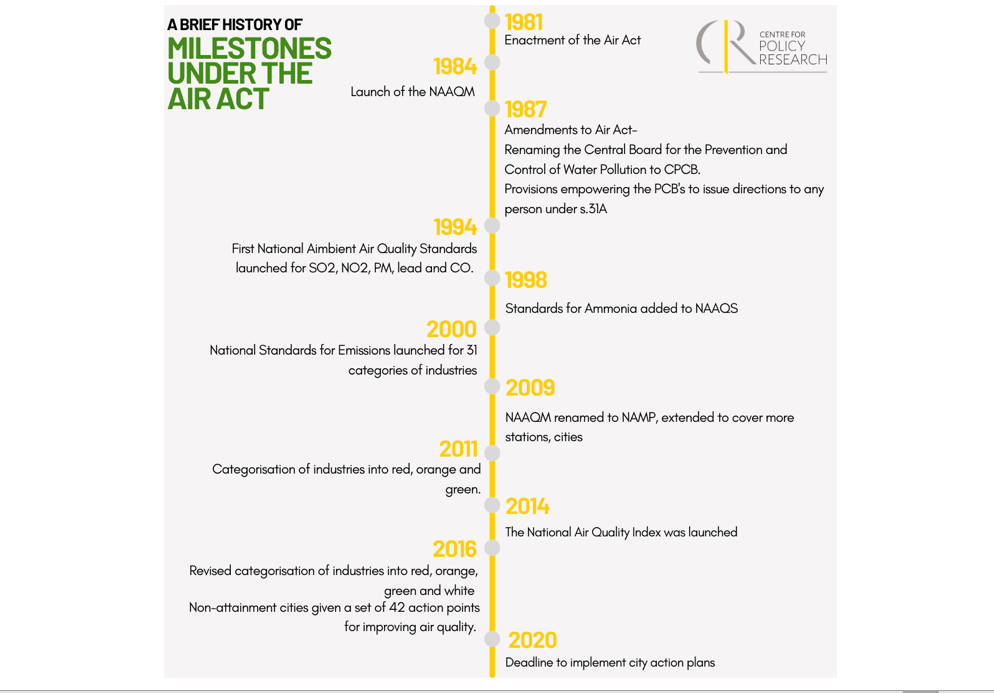

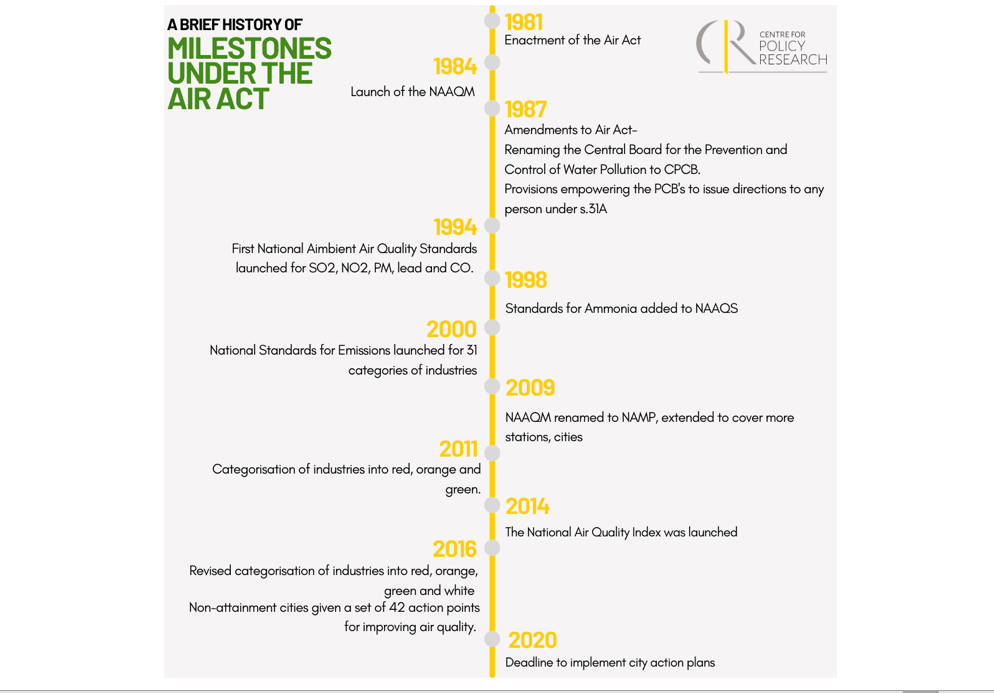

In 1984, the CPCB executed the first nationwide programme for monitoring of air pollutants under National Ambient Air Quality Monitoring (NAAQM). At the time, this programme was only being executed in seven stations at Agra and Anpara. This was later renamed the National Air Monitoring Programme and today it spans across nearly 800 stations in 344 cities.

The Air Act also provides a regulatory mechanism which requires polluting industries to seek consent from the concerned SPCB prior to operation. The operation of the industry is contingent on the fulfilment of pollution mitigation conditions imposed by the SPCB. These consents granted are renewed from time to time and as per the Act, information relating to the consents are required to be publicly accessible. Thus, any person aggrieved by the grant of such a consent or challenging compliance with the conditions mentioned in the consent may move an application before the Appellate Authority constituted under the Air Act.

Using its powers under the Air Act, the CPCB developed the ‘National Ambient Air Quality Standards ’ for twelve parameters, including SOx, NOx, particulate matter and ozone. Compliance with these standards is a mandatory condition in most consent applications and may also form the basis for directions issued by PCBs under Section 31A of the Act. For instance, the Delhi Pollution Control Committee issued a ban on bursting and selling of firecrackers so as to prevent air pollutants from going beyond the prescribed standards. Similarly, section 31A directions have been issued to prevent burning of solid wastes, implementation of plans such as the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) and even to ensure redressal of complaints about non-compliance with air quality standards.

In the decades since its promulgation, the Air Act has only been amended once substantively, despite evidence of several gaps in the legislation. First, the legislation relies on criminal prosecution as the primary tool for enforcement. The time-consuming litigation, the PCBs’ insufficient capacity to pursue them and low conviction rates in these cases make criminal prosecution an inefficient enforcement tool. This is evidenced by the fact that Delhi didn’t file a single criminal case under the Act in 2019, despite being one of the world’s most polluted cities. Amending the law to enable PCBs to levy penalties under the ‘Polluter Pays Principle’ could address the issue of ‘delayed and inadequate action’ against polluters.

Second, the Air Act not being updated, The Act does not provide for stable funding for the PCBs, compromising their ability to engage in critical air quality management tasks. While some PCBs heavily rely on own-resources through consent fees, NOC, and water cess, others depend on external funding. This results in disparities in funds across states, as more heavily industrialized states like Maharashtra and Karnataka have greater fund generation through consent fees. Finally, unfilled vacant positions of critical posts, such as the Chairperson, are a direct result of no time-limit set for their re-filling by the Act. The Act also does little to provide for more people with technical experience to be recruited on the Boards. As a consequence, most boards are often dominated by members from the state bureaucracy.

The legislation has also failed to match the pace of developments in science and air quality management research. The Act does not suitably reflect an airshed approach, despite the consensus that air pollution transcends administrative boundaries. This results in, for instance, Uttar Pradesh’s PCB lacking the mandate to file a case against polluters in New Delhi, thereby rendering the penal structure toothless for prosecuting polluters. The Act also fails to include health risks as a factor to be considered in the regulatory framework.

The Air Act in its current form no longer serves its intended purpose. However, recent movements in air quality management provide hope for focused action through legislation. In early 2021, news hit about a plan to overhaul the three main Environment legislations in India and create a consolidated ‘Environment Management Act’. This provides a potential opening to institutionalize elements that the Air Act presently lacks – an airshed approach, an effective penalty mechanism that deters violators, and adequately empowered PCBs. In sum, it is undeniable the air pollution in India is now a greater battle than the Air Act is equipped to handle.

(Environmentality is a collection of ideas, perspectives, and commentary by researchers at the Initiative on Climate, Energy and Environment, Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. Views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely those of the authors. They do not represent institutional views.)