The Indian Act is the principal law through which the federal government administers Indian status, local First Nations governments and the management of reserve land and communal monies. The Indian Act does not include Métis or Inuit peoples. The Act came into power on 12 April 1876. It consolidated a number of earlier colonial laws that sought to control and assimilate Indigenous peoples into Euro-Canadian culture. The Indian Act has been amended many times over the years to do away with restrictive and oppressive laws. However, the Act has had historic and ongoing impacts on First Nations cultures, economies, politics and communities. It has also caused inter-generational trauma, particularly with regards to residential schools.

January 01, 1755 First Indian Department The British create the first Indian Department to manage affairs between the colonial government and Indigenous peoples. After Confederation, the British transferred this responsibility to the Canadian government. (See also Federal Departments of Indigenous and Northern Affairs.)

October 07, 1763 King George III's Royal Proclamation The Royal Proclamation of 1763 lays down the basis for how colonial administration would interact with First Nations peoples in the centuries that followed. The Proclamation guarantees certain rights and protections for First Nations peoples, and establishes the process by which the government could acquire their lands. It also provides guidelines for negotiating treaties on a nation-to-nation basis.

August 10, 1850 Act for the better protection of the Lands and Property of the Indians in Lower Canada This 1850 law is one of the first pieces of legislation that includes a set of requirements for a person to be considered a legal Indian— a precursor to the concept of “status” that came with the Indian Act in 1876. The 1850 Act says that people “shall be considered as Indians” if they are of “Indian blood” and are members of a “Body or Tribe of Indians.”

June 10, 1857 The Gradual Civilization Act The Gradual Civilization Act requires male Status Indians and Métis over the age of 21 to read, write and speak either English or French, and to choose a government-approved surname. It awards 50 acres of land to any “sufficiently advanced” Indigenous male, and in return removes any tribal affiliation or treaty rights.

March 29, 1867 Federal Responsibility Under the Constitution Act (British North America Act), the federal government takes authority over First Nations and land reserved for First Nations (see Reserves). This authority would later extend to education of Status Indians.

June 22, 1869 Gradual Enfranchisement Act Along with the Gradual Civilization Act, the Gradual Enfranchisement Act aims at removing any special distinction or rights of First Nations peoples to assimilate them into the larger settler population. The government begins unilaterally enfranchising First Nations people. The fact that only one person voluntarily franchised under the Gradual Civilization Act suggests that Indigenous response to the colonial law was unfavourable. Efforts to assimilate Indigenous peoples to Euro-Canadian culture were always met with resistance on behalf of Indigenous people and their communities.

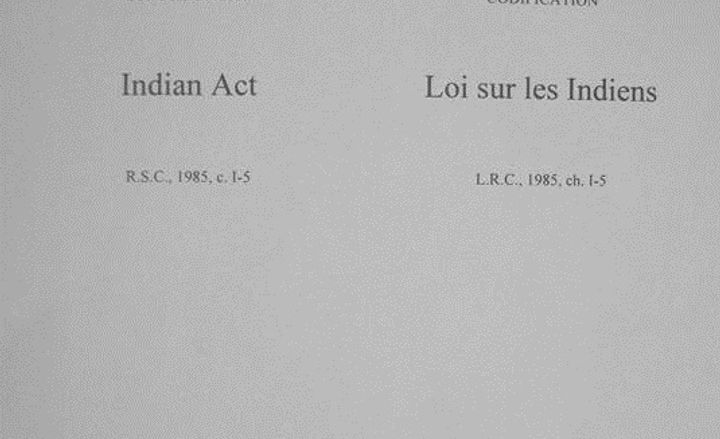

The First Numbered Treaty Is Signed A number of Indigenous groups made treaties— in particular the first five Numbered Treaties — with Canadian governments before the 1876 passing of the Indian Act. Those groups may consider their legal identity as First Nations people to flow through those treaties, rather than through the Indian Act.

April 12, 1876 Indian Act Becomes Law The Indian Act is introduced. The Act aims to eradicate First Nations culture in favour of assimilation into Euro-Canadian society. The Indian Act does not directly pertain to non-status peoples, including the Métis and Inuit.

January 01, 1880 Amendment to the Indian Act (1880) An amendment to the Indian Act formally disenfranchises and disempowers Indigenous women by declaring they “cease to be an Indian in any respect” if they marry “any other than an Indian, or a non-treaty Indian.”

Potlatch and Tamanawas Banned The federal government outlaws the potlatch ceremony and Tamanawas winter dances of Indigenous peoples in British Columbia, bowing to pressure from missionaries.

April 19, 1884Creation of Residential Schools Amendments to the Indian Act of 1876 provide for the creation of residential schools, funded and operated by the Government of Canada and Roman Catholic, Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian and United churches.

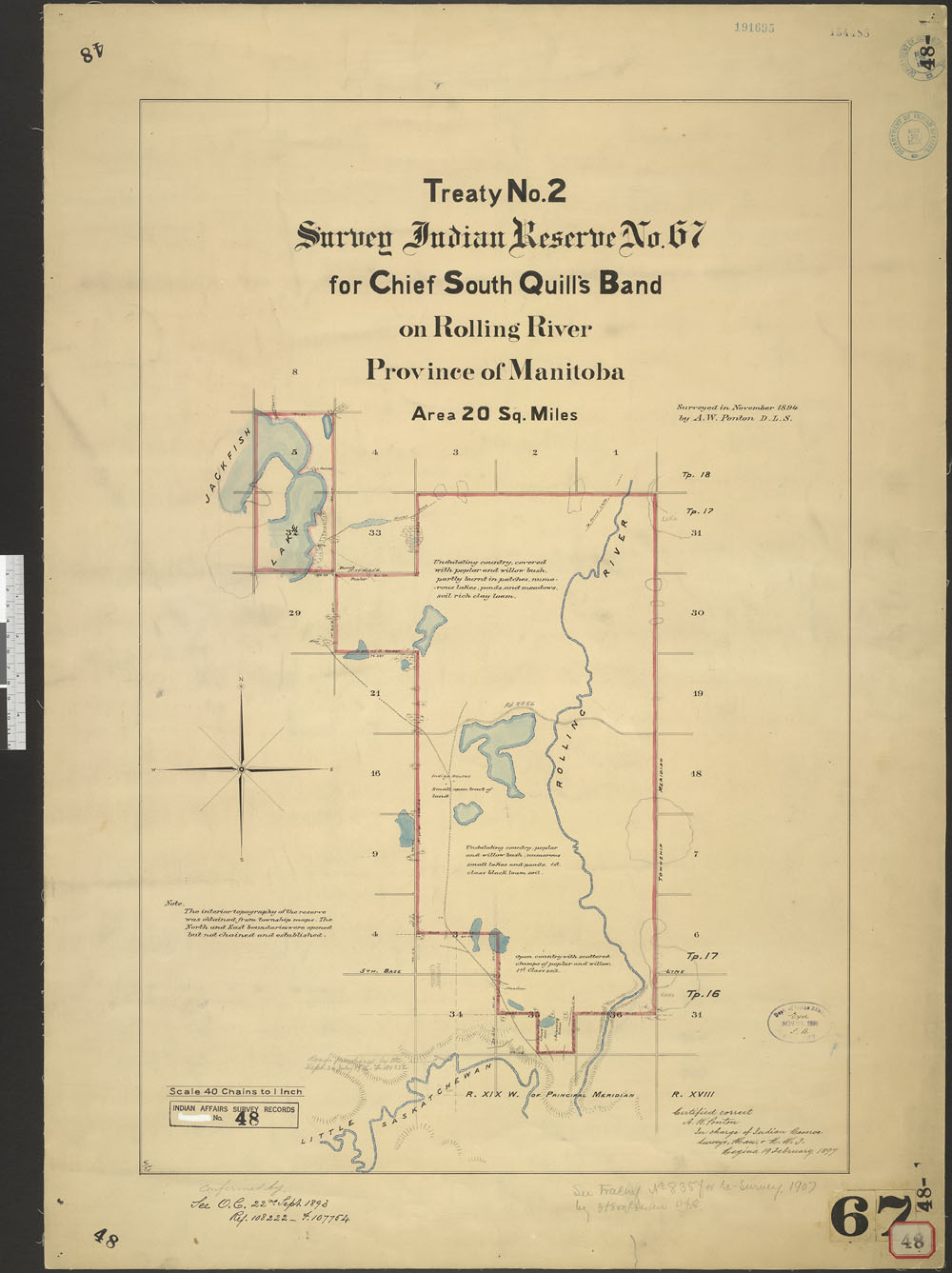

August 01, 1885

Creation of the Pass System Though not a law, the pass system prevents the movement of First Nations peoples off reserves. Together with the Indian Act, the pass system is part of an overall policy of assimilation.

July 22, 1895 Amendment to the Indian Act (1895) The 1895 amendment prohibits the celebration of “any Indian festival, dance or other ceremony.” Powwows, the sun dance and ghost dance are banned under this amendment. Another amendment in 1914 outlaws dancing off-reserve, and in 1925, dancing is outlawed entirely.

February 26, 1920 Indian Act Amendment Allows for Forced Enfranchisement of Status Indians The Indian Act is amended to allow for the forced enfranchisement of First Nations whom the government thought should be removed from band lists. Enfranchisement was the most common of the legal processes by which First Nations peoples lost their Indian Status under the Indian Act.

March 31, 1927 Amendment to the Indian Act (1927) The amendment makes it illegal for First Nations peoples and communities to hire lawyers or bring about land claims against the government without the government’s consent.

September 04, 1951 New Version of the Indian Act (1951) Indigenous lobbying leads to a new Indian Act that gives elected band councils more powers, awards women the right to vote in band elections, and lifts the ban on the potlatch and sun dance. However, the 1951 Act did not alter the terms of Indian Status for women; male lines of descent are still privileged. Furthermore, the Act introduces the “Double Mother” clause, which takes away status from a person whose mother and grandmother acquired status through a marriage. (See also Women and the Indian Act.)

The Sixties Scoop As residential schools closed, thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their families by provincial and federal social workers and placed in foster or adoption homes. Often, these homes were non-Indigenous. Some children were even placed outside of Canada. (See also Sixties Scoop.)

July 01, 1960

Right to Vote for Status Indians Status Indians receive the right to vote in federal elections, no longer losing their status or treaty rights in the process. (See also Indigenous Suffrage in Canada.)

January 01, 1969

White Paper Published A federal White Paper on Indian Affairs proposes abolishing the Indian Act, Indian status, and reserves, and transferring responsibility for Indigenous affairs to the provinces. In response, Cree chief Harold Cardinal writes the Red Paper, calling for recognition of Indigenous peoples as “Citizens Plus.” The government later withdraws the proposal after considerable opposition from Indigenous organizations.

December 07, 1970 Royal Commission on the Status of Women The hearings of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada begin in 1967 as a direct result of the coordinated efforts of various women’s organizations. These groups repeatedly called for sovereignty over their own bodies, constitutional reform and equality under the law. While the findings of the RCSW in 1970 recommended “that the Indian Act be amended to allow an Indian woman upon marriage to a non-Indian to (a) retain her Indian status and (b) transmit her Indian status to her children,” the change was not adopted.

Native Women's Association of Canada Founded The Native Women's Association of Canada (NWAC) was founded by Indigenous women and their allies, including non-Indigenous feminists active in the women’s movement. Members concerned themselves with the preservation and continuation of Indigenous culture on a local level, while focusing nationally on addressing the inequity in status conditions for women under the Indian Act. NWAC's first president was Métis war veteran and activist Bertha Clark Jones.

January 31, 1978 Self-government and the Indian Act The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement — as well as the Penner Report — resulted in the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act, 1984, the first piece of Indigenous self-government legislation in Canada, which replaced the Indian Act and established Indigenous communities in the region as corporate entities. Self-governing First Nations are not subject to the Indian Act, though the federal government continues to administer certain First Nations affairs.

United Nations Human Rights Committee Indigenous rights advocate Sandra Lovelace Nicholas takes her case about discrimination in the Indian Act (Lovelace v. Canada) to the United Nations Human Rights Committee. She argues that the Act violates international law. The UN rules in her favour, stating that Canada is in breach of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. While the UN lacks the power to change Canadian law, many Indigenous women in Canada see this as a victory.

April 01, 1982 Assembly of First Nations is Formed The Assembly of First Nations is formed out of the National Indian Brotherhood to promote the interests of First Nations in the realm of self-government , respect for treaty rights , education , health , land , and resources.

April 17, 1982 Canadian Constitution is Patriated The Canadian Constitution is patriated, and thanks to the advocacy of Indigenous peoples, Section 35 recognizes and affirms Aboriginal title and treaty rights. Later, Section 37 is amended, obligating the federal and provincial governments to consult with Indigenous peoples on outstanding issues. (See also Duty to Consult.)

April 01, 1985 Indian Act Amendment to Restore Status (1985) Bill C-31 amends the Indian Act to address gender discrimination in the Act. The Act no longer requires women to follow their husbands into or out of status. Women who “married out” could apply for the reinstatement of status rights. The work of First Nations women like Jeannette Corbiere Lavell and Sandra Lovelace Nicholas helped make change a reality. However, Bill C-31 limited the ability to transfer status to one’s children. The bill created new categories of Status Indian registration – 6(1) and 6(2) – and stipulated that status cannot be transferred if one parent is registered under section 6(2). In what is known as the “Second-Generation Cut-Off rule,” children would no longer be eligible for status after two generations of intermarriage with non-status partners. (See also Women and the Indian Act.)

November 21, 1996 Final Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples The 1996 report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples stated that many of the Indian Act’s measures were oppressive, and noted that “Recognition as 'Indian' in Canadian law often had nothing to do with whether a person was actually of Indian ancestry.”

December 12, 1996 Failed amendments to the Indian Act The federal government proposed several amendments to the Indian Act that dealt with band powers and governance. The first of these was Bill C-79 in 1996, followed by Bill C-7 (2002) and Bill S-216 (2006). While all of these bills failed, some First Nations have made other agreements with the federal government, known as sectoral arrangements, that allow for greater governance powers not provided under the Indian Act. Some examples include the First Nations Land Management Act (1999) and the First Nations Fiscal Management Act (2005).

November 12, 2010 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples In 2010, Canada endorses UNDRIP as an “aspirational” document. After a change in federal government, Canada signed UNDRIP in May 2016.It has yet to be seen how Canada will implement this agreement.

Amendment to the Indian Act (2011) Bill C-3 comes into effect. It is the federal government’s response to the McIvor case. Bill C-3 grants 6(2) status to grandchildren of women who regained status in 1985. However, Bill C-3 did not completely rid the Act of discrimination. The descendants of women, specifically in terms of great-grandchildren, did not have the same entitlements as descendants of men in similar circumstances. Therefore, some individuals were still denied status rights because of gender discrimination. (See also Women and the Indian Act.)

April 14, 2016

Supreme Court Ruling Changes Legal Definition of “Indian” The Supreme Court of Canada rules unanimously that the legal definition of “ Indian ” — as laid out in the Constitution — includes Métis and non-status Indians . While this ruling did not grant status to Métis and non-status Indians, it helped facilitate possible negotiations over traditional land rights , access to education and health programs, and other government services.

December 22, 2017 Amendment to the Indian Act (2017) The first part of Bill S-3 is brought into effect. Bill S-3 is made in response to the 2015 Descheneaux case about discrimination in the Indian Act. Among other provisions, the amendment enables more people to pass down their status to their descendants and reinstate status to those who lost it before 1985. (See also Women and the Indian Act.)

August 15, 2019 Amendment to the Indian Act (2019) The second part of Bill S-3 — related to restoring status to women and their offspring who lost status before 1951 (known as the “1951 Cut-off”) — is brought into force. According to the government, “All known sex-based inequities in the Indian Act have now been addressed.” (See also Women and the Indian Act.)