Email etiquette is a common struggle for students. It's important to nail down, though, because the professors on the other end of your emails are etiquette professionals. And while that's a little more than intimidating, it also means that we can go directly to the source—real-life professors!—to learn how to email a professor.

The professors we contacted gave comprehensive responses full of wonderful and thoughtful feedback that will help students write better emails. Many themes recurred, and it was often easy to tell that the professors had strong feelings about certain etiquette matters.

From tips on salutations to content and everything in between, these professors have provided advice to help you with emailing your professors based on real-life scenarios.

They've seen the worst of your emails; they've seen the best of your emails. So what's the takeaway?

It's important to be self-aware when you're composing an email. If you have a firm grasp of the English language, you should be able to write a grammatically correct email in which everything is spelled appropriately, the word choice is academic, and the tone is appropriate.

However, the English language is tricky, and nailing down the minute details can be difficult. If you struggle with grammar or tend to overlook errors, it will be difficult to communicate professionally with your professor. As such, you may wish to have your writing proofread to ensure that your email is completely error-free.

Dr. Brandon Gilroyed, an anaerobic digestion and biofuel research assistant professor at the University of Guelph Ridgetown Campus, notes the importance of proper spelling and grammar when emailing a professor: "I have seen plenty of emails written entirely in lowercase and without any punctuation, likely because the message was written on a smartphone."

While writing on your phone might be more convenient, Dr. Gilroyed states that it still denotes poor etiquette. "It is difficult to take the sender of a message riddled with spelling and grammatical errors seriously," he says.

Having a firm grasp of the English language doesn't end with spelling and capitalization. Clarity in the content of your email is vital if you want your professor to respond positively. If an email isn't well written, it can be difficult to understand its content.

Dr. Ted Vokes, an adjunct faculty member in the Department of Psychology at the University of Windsor, has taught more than 100 courses, between the Department of Psychology and the Odette School of Business. So he understands the difference between a well-written and poorly written email. He says, "If it's worth sending the email, it's worth reading over before one sends it. I really want to help students, but if I can't understand the question, I am at a loss as to how to help."

Here's another tip where self-awareness is key. Email using your student email address, if you have one. If you don't or you can't use it for some reason, be very conscious about what your private email address is communicating to your professor. I had to change the email address here for privacy reasons, but I can tell you that Dr. M.J. Toswell, a professor in the Department of English at Western University, noted that she once received an email sent from an account as unprofessional as "fuzzypyjamas@example.com," which is her "best example of a bad email account." Agreed!

Clearly, an email address like this doesn't send a professional message to your professor, and etiquette is all about professionalism. However, there's an even bigger problem with using private email accounts: spam filters. Dr. Toswell recounts:

My all-time favorite was a sequence from last year, on a Friday evening. The first email at 8 p.m. asked me whether an assignment was really due online on Monday night. The second email at 9 p.m. asked why I hadn't answered the first email yet. Both were addressed "Hey" and sent from a private email address that landed in my spam so I didn't see them until Saturday morning, and nearly deleted them because the subject line was blank too.

So the best-case scenario is that you lose that much-needed professionalism, and the worst-case scenario is that your email winds up unread. Be very aware of the email address you use to email a professor, and carefully consider what it might be communicating.

Most of the professors noted that students often already have the information they're seeking before they send an email. Dr. Toswell emphasizes that her "biggest woes" are related to the importance of checking the information that's already available to you before you start sending emails.

She notes that students often ask where or when exams are, what content is included on exams, or even to be exempt from exams, all just hours before an exam is set to begin. Dr. Toswell says, "It's hard to explain politely that the course materials, the syllabus, and my in-class discussions have covered these issues, and they should look at the website."

Clearly, it's best not to email your professor for information that is already available, but you may not realize the information is available. Be sure to listen in class, check the course website, and refer to the syllabus before you email a professor. Dr. Manina Jones of the English and Writing Studies Department at Western University notes that a recurring theme she and her colleagues encounter is students asking questions the course syllabus can answer.

She advises, "Before shooting off that email, it can never hurt to read carefully over the syllabus to see if the information is included there." This will ensure you won't come across as inattentive or lazy to your professors, which will not give the best impression if you're asking a question or requesting a favor. Dr. Jones also hints that checking the syllabus also applies to salutations: "Often the syllabus will give the professor's preferred form of address." On that note . . .

Since the salutation of an email is usually only a couple of words, it's easy to overlook. However, the salutation requires careful consideration, especially since it's the first line of your email.

First, make sure you include one! "I have to say that the lack of any salutation (launching right into 'I want . . .' or 'Where is . . .' or 'Can I . . .') . . . is the quickest way to get my back up before I even read the body of the message," Dr. Jones states. Some kind of greeting comes off as more friendly, polite, and professional.

Dr. Gilroyed notes that it's common to get emails that are too casual, beginning simply with "Hey." Dr. Jan Plug, Associate Professor and Director of the Centre for the Study of Theory and Criticism at Western University, agrees that students should avoid addressing their professors this way. He states, "Of course, all of this depends on how well the student knows the professor, but when starting a conversation, a bit too much formality might not be too much." He suggests using a simple "Dear" or "Hello" instead. "Things may get more familiar over time, but you really can't go wrong starting off in this way."

Dr. Vokes notes that a casual greeting, though, can be appropriate in some situations. Consider how well you know the professor. If you've already corresponded with this professor through email and in class, you may wish to use a more casual greeting. Dr. Vokes states, "I'm totally fine with 'Hi Dr. Vokes.' I set a casual tone in class, so I'm pleased when students feel comfortable to ask questions via email or in person in this manner."

He notes that there's a fine line, though: "What I never appreciate is something like 'Hey! Is there class tonight?' Once I even had a student send me an email which said, 'Hey, dude . . . do we have to come to class today?' (it was snowing out)." He suggests that it doesn't give the best first impression to receive an email that begins, "Hi Ted." Dr. Jones agrees: "I've often had emails starting 'Hey' or 'Yo!' or 'Dude!' This is fine for friends but not appropriate for an email to your professor."

The way you address your professor communicates something both about you and about the person you're emailing, so it needs attention. Dr. Jones notes that your email "requires a formal salutation and a recognition of the professor's professional status (and your own!)."

In addition, Dr. Plug says that "students can tend to be too familiar in their email style too quickly." You need to address your professor correctly, of course, carefully considering his or her title. If your professor has a doctorate, he or she might not want to be called "Professor." Similarly, he or she might not appreciate a "Mr." or "Mrs." and might prefer being addressed as "Professor."

It's also best to avoid gendered addresses. The female professors contacted often cited taking issue with the address of "Mrs." Dr. Jones states it is "a particularly irritating salutation because it makes assumptions about my marital status and gender role." Similarly, Dr. Toswell notes that she hates being called Mrs. Toswell so much, "it's visceral." That's definitely not the kind of reaction you want to garner from a professor!

In the same way, addresses like "Sir" can come across as unprofessional in emails to your professor. "I often get 'Sir,' which is fine, but it clearly conveys to profs that you still think you are in high school," Dr. Vokes notes.

Dr. Vokes does say, however, that he understands how addressing professors appropriately is confusing to students: "Not all professors are doctors . . . and not all doctors who teach are professors . . . . I'm sessional, but because I've been made an adjunct, both are accurate. Then, of course, senior graduate students who teach are neither, and 'Mr.' or 'Ms.' is appropriate." It's confusing, but that also means that, when you get it right, your professors will both notice and appreciate your time and effort in addressing them correctly.

You have to think about the actual name you'll use to address your professor. Obviously, you want to spell his or her name correctly. There will be no great reward for this, but spelling a name incorrectly comes across as extremely disrespectful. Usually, a last name is included in the email address, so there's no excuse for spelling the name incorrectly in the body of the email. Dr. Vokes says, "I got 'Dr. Votes' just this morning. I understand autocorrect is likely the culprit in this case, but I get 'Bokes' and 'Voakes.'" While he notes that he's not offended in these cases in the slightest, he also notes, "It leaves the impression that this person isn't that attentive to detail."

In addition, spelling the professor's email address correctly is vital. Dr. Jones states, "Because my last name is common, I've even had emails meant for another professor altogether," so make sure you check that you have the appropriate address.

On actually using your professor's name in the email, Dr. Gilroyed notes that greeting a professor by his or her first name is fine if it's agreed upon in advance, but doing so otherwise is improper email etiquette. He says, "The first email communication between student and professor is not a good time to begin using the first name."

When in doubt, Dr. Jones notes that professors will tell you outright if they prefer to be addressed by their first name. If you're still unsure, she advises that "the more formal choice of salutation will never offend, and then you can be corrected (it's easier to say, 'Please call me Bob' than it is to say, 'Um, I'd rather you didn't call me Bob')."

Dr. Plug also notes that, after the first email, you can begin to follow the professor's lead, and Dr. Jones agrees. In my original email to Dr. Jones, I addressed her as "Dr. Jones," safely choosing a more formal address. After she signed off as "Manina" in her reply, it was safe to assume I could henceforth address her as "Manina," which I did in my subsequent emails. She took note of this in returning tips to me, so it actually works! Reading signs carefully will help you to choose the correct address.

When emailing professors, you have to remember that they receive tons of emails every day. These emails come from different students in different classes, sometimes in different faculties, or even from different campuses.

When you email your professor and don't identify yourself properly, your professor might have trouble placing you. Being remembered when you're just one student in a huge class is an even greater concern if you have a common name. Dr. Gilroyed notes that "in larger classes, there might be three students named Matthew or five students named Jessica."

Dr. Jones similarly states that she sometimes teaches many big classes in the same semester and that knowing the name of every student is difficult. That doesn't even include problems across different classes or sections! So it's imperative that you place yourself exactly and fully. Including your first and last name, class, class time and day, and section number will help a professor to place you correctly. Dr. Jones notes that you can also provide context in terms of continuing a previous conversation or building on a topic you've already discussed in person.

In addition, you have to provide background information in terms of the actual topic at hand. Dr. Gilroyed says, "Students often write emails in which they immediately focus on a very specific topic or detail without providing any context or preamble. While the content of the message may be perfectly clear to the student, a professor who has dozens or hundreds of students may need more information to understand the scope of the student's query." He also notes that fully explaining a situation is "better than assuming your professor will know or remember every detail immediately."

If you've already emailed and spoken to your professor and have established a more casual correspondence, your messages might read awkwardly if they're too formal. Professors encourage being casual in this case. However, it's vital to note the difference between being casual and being careless.

You should never resort to texting language. Obviously, it's unprofessional. Dr. Gilroyed notes, "Use of this kind of language communicates to me that a student doesn't wish to spend the time to construct a proper message, yet they will often want me to spend my time reading the message and then doing something for them."

Similarly, Dr. Jones says that it's inappropriate to use short forms and emoticons. This also means the difference between correctly written English and emails riddled with typos. Dr. Vokes comments that, after a respectful salutation, "clear and respectfully written information in the body of the email needs to follow." There's a difference between a casually written message and an incorrect and careless one.

There's also a difference between being casual and being careless in terms of content. Your professor does not want to know too much information; even if he or she is friendly with you, some talk should be reserved for friends only. For example, Dr. Jones notes that she receives emails from students offering excuses for missing class that simply give too much information. "I don't need to know that a student's friends threw him a birthday party and he's hung over and wants to write a make-up test, or that she's decided to take a long weekend, or was stuck in traffic," she says.

Though this tip isn't directly related to email etiquette, it's been included because it was mentioned by multiple professors without prompting and it does concern the content of your email. Several professors noted a certain question they're commonly asked that drives them absolutely nuts. Students who miss class will often ask, "Did I miss anything in class on Monday?" Dr. Plug says, "I always want to say, 'No, we did absolutely nothing, as usual.'"

Dr. Jones notes that the same question is "the great bane of all professors." She offers this poem that tackles the subject. Why is it such a terrible question, though, and what makes it so inappropriate? Professor Jones offers an answer:

First, it's insulting to imply that the content of any class might not have been important, or that it can be recapped in a short email—and second, it's not the professor's responsibility to offer multiple iterations of the class. If you miss a class without a legitimate reason, it's your responsibility to arrange for access to notes from another student and/or find out what was covered.

Clearly, it's best to avoid this question!

Before you sign off, it's important that you include a valediction—that is, a complimentary farewell. Dr. Jones notes the importance of a valediction in proper email etiquette, even if it's just a quick statement like "Thanks for your help!" She says, "It does pay to acknowledge that if you're asking for something (even if it's just information) that your professor deserves some recognition of his/her time and trouble."

Instead of launching directly into what it is you want to request from your professor, you can acknowledge your gratitude or how busy he or she is. Doing so is a nice little way to recognize the professor's efforts in replying to your emails, and the gesture will be appreciated. Dr. Jones provides an example of an effective valediction: "Try something like 'I know you're busy, but I'm hoping you'll be able to make some time to meet and go over my answers on the quiz.'"

It might seem like a small or insignificant note, but it can definitely help your email to be received in a positive light and paint you favorably, especially amongst a slew of emails that don't include valedictions. Dr. Vokes notes, "From research, we know that first impressions very much affect a person's desire to be of assistance." If you make a good first impression, your professor will be more likely to help you, or, at the very least, they will be happier to help you.

Your signoff is as important to consider as anything else in emailing a professor. Just like your opening salutation, it communicates something about you. You'll also be able to further set the tone of the email, be it more formal (using something like "regards") or more casual (using something like "all the best"). Offering "cheers" will not always be appropriate, so again, consider how well you know the professor you're emailing.

Dr. Gilroyed states, "Every email to a professor should adhere to the standard construct of a letter, which includes an opening salutation, the body of the message, and an appropriate signoff." That's why using an improper signoff, or no signoff at all, is bad email etiquette and should be avoided. A simple signoff is fine; try to balance being casual and professional.

You can also use your signoff to further distinguish yourself among a sea of students. Dr. Gilroyed notes that students should sign off "with an appropriate closing salutation and then a full name." Again, professors receive many emails every day. Some are without signoffs, and some use only first names. Including your full name will help your professor recognize and identify you quickly and easily.

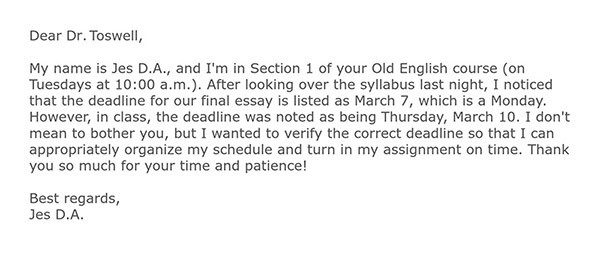

Okay, now that we have a list of email etiquette tips from real professors, how about putting them into practice? Here's an example of an excellent email to a professor:

An email isn't just a piece of correspondence. It's an exercise in communicating well, and you're judged by it. Using this advice from real professors about how to email a professor, you can be judged favorably. Dr. Gilroyed says, "I cannot speak for all professors, but I certainly take notice when I receive a well-constructed email from a student. It shows me that they care enough to put in the effort to compose a proper message and they respect my time."

Even better, you can use emailing a professor to your advantage by asking genuine and intellectual questions. As Dr. Toswell explains, "Don't use up what I think of as your email currency (there's only so much bandwidth in my brain for one student and her questions unless they genuinely engaged with the course material) on bad inquiries." What's more, you can use these questions to form a bond with your professors. Dr. Toswell further says, "Email in order to establish a connection, and make it a solid one." If your email follows these tips, you'll no doubt be able to establish a connection that lasts through university and beyond.

Special thanks to all the professors who shared their email etiquette tips with us for this article. Your time and insights are much appreciated!

Image source: Nosnibor137/BigStockPhoto.com

Jes is a magician and a mechanic; that is to say, she creates pieces of writing from thin air to share as a writer, and she cleans up the rust and grease of other pieces of writing as an editor. She knows that there 's always something valuable to be pulled out of a blank page or something shiny to be uncovered in one that needs a little polishing. When Jes isn 't conjuring or maintaining sentences, she 's devouring them, always hungry for more words.